What Kilimanjaro taught me about software development

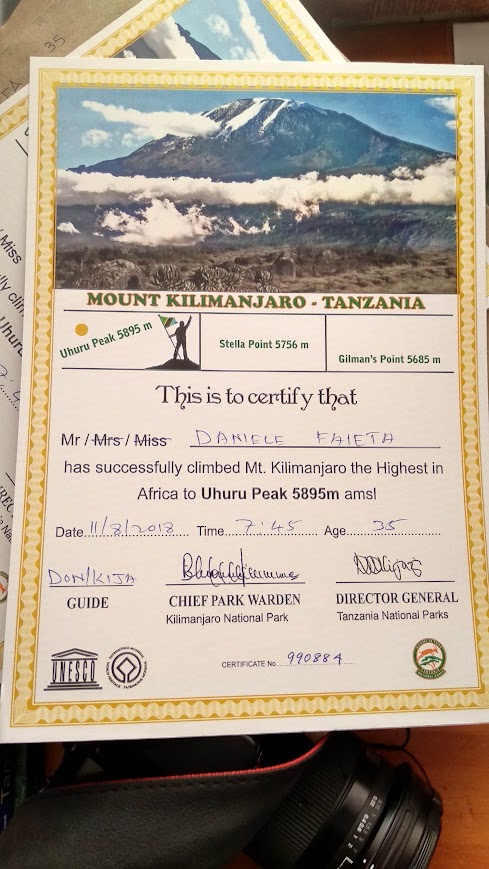

At dawn on August 11th, 2018, I reached 5895 meters at Uhuru Peak, the highest point of the tallest mountain on the African continent, the famous Mount Kilimanjaro.

I decided to do the trek because of my passion for hiking and travels, because it was a difficult but not impossible challenge, and because it was simply proposed by a dear friend and I decided to throw myself into this adventure. No motivational nonsense in the style of “Awesomeness motivational posters” from Barney Stinson’s memory.

While sorting through some paperwork, I came across the little diploma they give to summiteers and I thought: isn’t it curious that the trek has many analogies to software development? What did I learn?

Get well organized

Preparation for the trip is fundamental: costs are high and a single wrong choice can compromise everything. We chose a local agency recommended by our local alpine club section, with good references. Despite the confusing communication from the manager (“All is clear,” he wrote in each of the 50 emails exchanged, followed by an odd “Stay tuned for more details”), we decided to trust them and pay a substantial deposit. In hindsight, it was the best choice: everything went perfectly, and we saved a bit of money too.

Software development works the same way: without adequate planning (architecture, technologies, team, timing) the risk of not reaching the goal becomes high. Sometimes, you don’t even get started :)

Anyway, organizing is good, but then you need to be ready to solve problems and handle the unexpected.

Be decently prepared

To climb Kilimanjaro you need to be fairly fit. Nothing out of this world, but you need to be able to do hikes with 1000+ meters of elevation gain without being completely exhausted, and be able to do it for two, three consecutive days. It’s also important, if possible, to try to acclimatize before departure, as I did in the two previous weekends climbing to over 3,500 meters (Mount Vioz and Mount Cevedale).

In the same way, those who do software development must know the tools they use at a good level, and, if they don’t know them, must have the ability to learn and improve - in practice, they must train.

Step by step, without overdoing it

During the trek, the guides kept repeating “Pole pole” to us, which means proceeding at the right pace - that is, slow - step by step, enjoying the experience as much as possible. It was important not to overdo the pace and, believe me, I’ve never gone so slowly in the mountains. I was able to observe people who had instead chosen to cut a stage because they felt fit, maybe athletes obsessed with times, always looking at their watch instead of the landscape. Well, these people burned out after a few stages - altitude sickness doesn’t forgive.

With software it’s not so different: in the “quiet” phases of a project, things should be done the smart way, thinking, without rushing, favoring quality, to be ready when you need to push and to avoid burning out too soon.

Managing difficulties (1)

One point in particular of the trek worried me: the so-called Barranco Wall. A small wall of about 300 hundred meters to climb after the Lava Tower stage (first time at 4400 meters, potential altitude sickness problems). Given my reluctance to put my hands on rock and the discomfort I feel with exposure, before leaving I tried in every way to understand what would await me, but it simply wasn’t possible. Well, on the fateful day I told myself “Let’s do this, zero stress” and everything went well. After all, there was no other solution, right? But it was so easy that I felt a bit silly for overestimating the situation.

It’s the same with software: it’s important not to worry too much before you need to. A solution can always be found - after all, it’s our job!

Managing difficulties (2)

On the other hand, during summit day I had many difficulties related to altitude sickness: nausea, fatigue, desire to stop (and turn back), excessive cold. To be clear, the summit stage is tough: you wake up at 11 PM after “sleeping” at 4600 meters in the afternoon/evening. You have breakfast, trying to eat and drink as much as possible. You get ready (put on all available clothing) and you leave. 1300 meters of very steep elevation gain, at night, with a headlamp, with freezing wind. If it hadn’t been for my guide Donovan helping me mentally, pushing me to stop as little as possible, and carrying my backpack, I wouldn’t have made it. I contributed my part, certainly, but his help was fundamental.

When working on a project there can be moments of difficulty: they should be shared with the team, you work on them together, you need to get help. After all, in a healthy team, commitment is collective - everyone has an interest in promoting the project’s success.

Enjoy the success

At dawn I finally managed to reach the edge of the summit crater, Stella Point. It would be just over an hour of walking, almost flat, to reach the summit. I felt bad, but not that bad, so I understood I would make it. I enjoyed the most beautiful sunrise of my life and then resumed walking while overcome with emotion. In my head I was singing the Kilimanjaro song, and every now and then I dried my tears to prevent them from freezing on my face. It was definitely one of the most emotional moments I remember.

Now, let’s not exaggerate: when a project ends and everything goes well, you don’t feel such strong sensations. However, it’s important to take a moment to fully enjoy a phase that’s concluding and maybe do it with the whole team (whether it’s a lunch, dinner - even when I was full remote we always did our best to get together). This is also how you make a team stronger, creating important human relationships that transcend the professional sphere.

The importance of team

To climb Kilimanjaro it’s mandatory (and extremely necessary) to pay for a team - these are the national park rules. The team must be composed of certified guides, porters, and a cook, and the number of people obviously varies based on how many intend to climb the mountain. For two people, anyway, you need 2 guides, at least 6 porters (plus 1-2 “phantom” porters) and a cook. Each with their precise tasks: the guides’ job is to always be by your side, set the pace, give you some information about fauna, flora and landscape, assist you in case of need. The porters leave later because they have to take down the camp and arrive earlier because they have to set it up again. The cook, obviously, cooks for everyone. Maybe it was the altitude, the fatigue, but believe me, I’ve rarely eaten so well in the mountains!

Without such a team you don’t reach the summit: it would be a challenge for world class athletes. It’s the same with software: cohesive team, each with their own space and tasks, continuous interactions, open dialogue. It’s the key not only to reach the end of a project, but to do it with satisfaction. My approach, just as it was during the trek, is to try to get to know each other better, talk, embrace diversity and establish human contact. A true professional is first and foremost a human being.

Pole pole

When Donovan told me “Pole pole” for the nth time, I thought it was just a way to keep me from burning out before the summit. In hindsight, it was much more: it was an approach to life and work. It’s not about running or proving something to someone, it’s about getting where you want to go in the best possible way.

I understood that climbing a mountain and developing software teach the same thing: technical competence is only part of it. The rest is knowing when to slow down, when to ask for help, when to admit “I can’t do this alone.” Whether it’s altitude sickness at 4,600 meters or a bug you can’t solve after three days, the principle doesn’t change.

Kilimanjaro is now behind me. I’ll keep on developing software. But at least now I know that if I’ve kept the right pace up there at 5895 meters in the icy wind and altitude sickness, I can tackle anything in front of a keyboard. Pole pole.

Links and resources

- Awesomeness motivational posters - When I get sad, I stop being sad and be awesome instead. True story!

- Top of Africa Expeditions - The local agency that guided us during the trek

- Kilimanjaro Machame Route - Detailed description of the ascent route we took

- Barranco Wall - Everything you need to know about the “little wall” that worried me

- The “Pole Pole” philosophy - A deep dive into the African philosophy of the slow pace

- Kilimanjaro’s Song - The little song I was singing in my head while climbing to the summit